Out now in the August issue of Hemispheres, the in-flight magazine of United Airlines, my feature “The Road Led to Rome” (linked below in the Further Reading section) was a year in the making—several years, really, if you consider how long my family has been talking about this trip. Unlike many expats who move to Italy, I don’t have Italian roots, but lately I’ve been thinking about a different kind of family connection to the country.

My grandpa, Ira Itzkowitz, enlisted in the army in 1943 and was stationed in Italy. Growing up, I heard stories about how he marched on Rome when the city was liberated from Nazi occupation in June 1944. For as long as I can remember, my dad has been fascinated by WWII history. On past trips to Italy, he made a point of visiting museums and monuments related to the war. Those were always one-offs though. This time, with a commission in hand to write this story, I decided to finally organize a multi-stop trip retracing Grandpa’s steps.

I won’t go into the whole story here—it’s better if you read my feature—but I do want to highlight a few places that didn’t make it into the story because there just wasn’t enough space to include everything we did.

Salerno and the surrounding area

Even though Grandpa didn’t arrive in Italy until early 1944, we started our trip in Salerno because that’s where the 36th Division (his division) first landed in September 1943. Our first evening there, we dined at Ristorante del Golfo, which opened on the port in 1943. In the hallway, they have photographs of what the port looked like back then.

Unfortunately, the Museo dello Sbarco e Salerno Capitale was closed due to structural issues with the building, but when I called to get some information, the museum’s president offered to meet with me. Professor Antonio Palo is a historian who has written books about the war, but to be honest I was most fascinated by his personal stories. His mother was evacuated from Salerno and sent to a hill town nearby and his father was a soldier in the Italian army. He was captured by the Germans and sent to a camp near Berlin, but managed to get out and returned to Italy on foot, at which point he joined the partisans in Bologna.

After my meeting with Professor Palo, we visited the Museum of Operation Avalanche in Eboli, which ended up getting cut from the story. We did a guided tour with the museum’s director, who cranked an old air raid siren, thrusting us back in time with its wail. We saw photographs, newspapers, and artifacts, before going into the “Emotional Room” and watching a multimedia presentation with video footage from the war.

Afterwards, we went to see one of the beaches in Paestum where Operation Avalanche took place. In our search to find a German bunker I’d read about, we ended up at a spartan beach club that was closed because of an electrical problem. The only people around were the owners, one of whom told us that he served General Mark Clark (head of the U.S. Fifth Army) at a restaurant where he worked in the ‘60s.

That evening we had dinner at Botteghelle 65, which opened in 1919 as a salumeria. Its new owner added tables and transformed it into a restaurant serving local products and recipes.

Caserta

From Salerno, we drove north to Caserta, which buzzed with activity during the war. We knew from his letters that Grandpa was sent to Caserta to rest after a fierce battle in Velletri, but we weren’t able to determine exactly where. According to Giovanni Cerchia, professor of modern history at the Università degli Studi di Molise, who I interviewed for the article, he was likely put up in a school or other administrative building that had been taken over for the war effort.

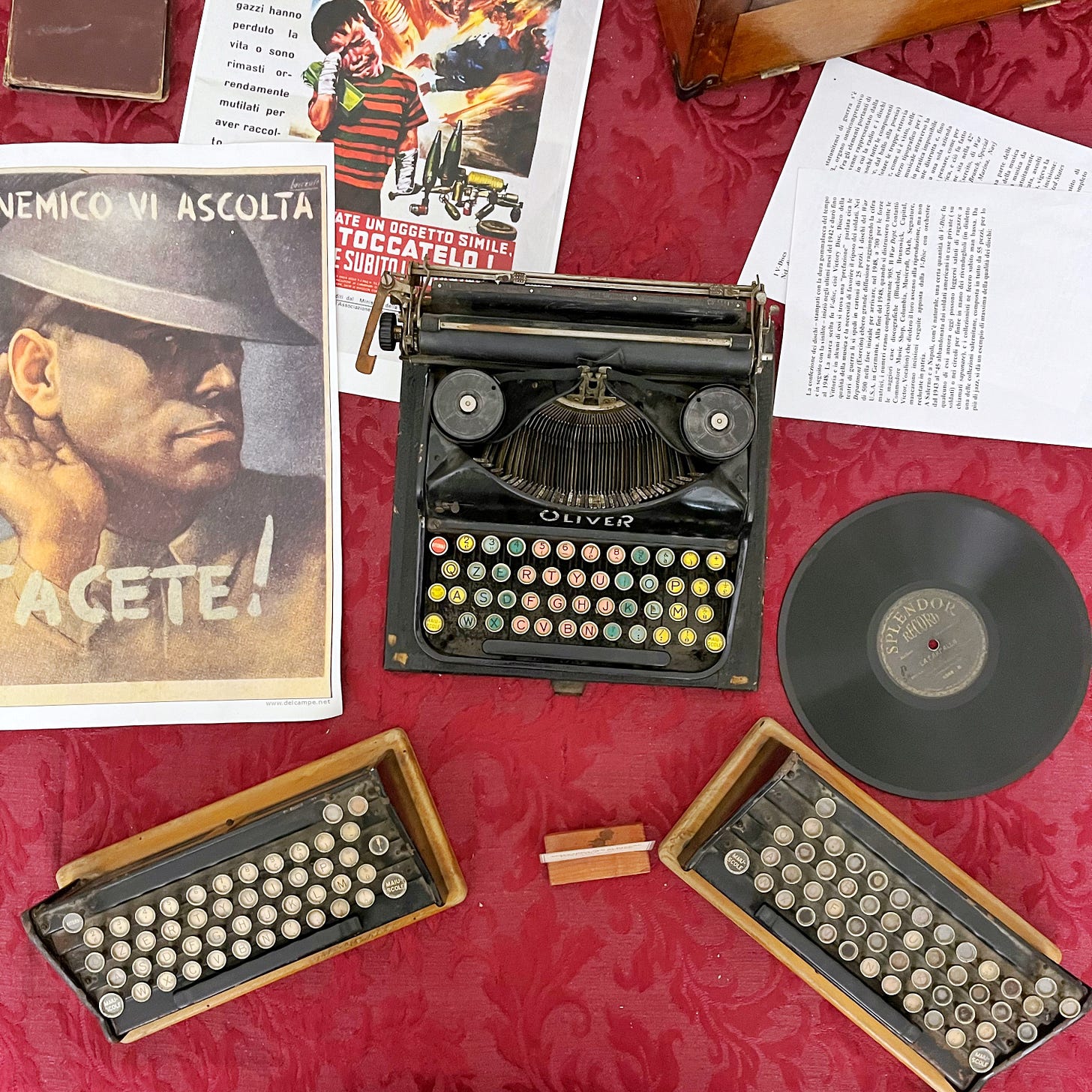

Meanwhile, General Clark set up his headquarters inside the Reggia di Caserta. Because I was on assignment, I managed to get special access to the off-limits attic inside the Reggia, where we saw graffiti and pin-up models torn out of the pages of magazines on the walls. In the first room was a collection of objects left over after the war ended.

For dinner that evening, we broke with the WWII theme and went to Pizzeria I Masanielli. Crowned the number one best pizzeria in Italy by the judges at 50 Top Pizza, it’s a must when in Caserta. My family agreed.

Cassino

Our next stop was Cassino, site of the Battle of Montecassino. I say battle, but it was really multiple battles over the course of several months. Cassino was an important point on the Gustav Line, the German line of fortifications that crossed the peninsula from Ortona to Gaeta and blocked the way to Rome. The Germans were camped out up on the mountain around the Abbey of Montecassino, where they could see everything happening below.

In what is still considered one of the most controversial events of the war, the American army bombed the abbey. Among the sources I consulted, there’s debate about whether the Germans were or weren’t occupying the abbey, and whether the Americans really believed the Germans were occupying the abbey, or if they bombed it regardless in order to break through the Gustav Line.

We visited an exhibition about the Gustav Line at the Museo Historiale di Cassino and then visited the reconstructed abbey. We also visited the Freedom Bell on the banks of the Gari River in Sant’Angelo in Theodice, where the deadly Battle of Rapido River took place.

Anzio and Nettuno

The next day, we continued to work our way to Rome, stopping in Anzio to visit the Museo dello Sbarco and meet the museum’s president, Patrizio Colantuono, who I quoted in my article. The museum is just one room, but it’s packed to the brim with photographs, newspapers, uniforms, weapons, and other artifacts collected over the course of decades.

After lunch at Pescheria Amore di Mare and a quick gelato stop at Gelateria Conforti, we drove ten minutes to Nettuno to visit the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery. I didn’t have enough space to include the cemetery in my article, but it was really moving. We did a guided tour with Luca, who brought us to visit the memorial, and when Taps started playing, we all choked up a bit.

More than 7,000 soldiers are buried there in neat rows marked by white crosses or Jewish stars—and that only represents about a third of the casualties; two-thirds of the deceased were sent home to their families and buried on American soil.

Rome

We ended the trip in Rome, just in time for the 80th anniversary of the Liberation, and visited some WWII-related sites that I didn’t even know existed before I started doing research for this article.

On June 2—the Festa della Repubblica—we did a guided tour with Elisa Valeria Bove, CEO of Roma Experience, starting at Piazza Venezia, where we watched the military planes flying overhead. We then trekked through the crowds and the rain to Via Rasella, near the Trevi Fountain, to learn about the partisan attack on Nazi troops in March 1943.

Knowing that the Nazis always marched up that narrow uphill street after lunch, the partisans planted bombs. When the Nazi soldiers didn’t show up at the usual time, they feared their plot had been discovered. Finally the Nazis came marching in, the bombs went off, and 33 Nazis and two Italians were killed, while soldiers shot blindly up at the buildings in the street.

There’s no plaque or sign, but if you walk part of the way up the street, you’ll see bullet holes in one of the buildings that were left there as a reminder of what happened. Afterwards, Elisa brought us to the Jewish Ghetto to give us more context about the city’s Jewish community and the Racial Laws that stripped them of the last of their dignity.

The next day, we met up with Valerio Caffio, a WWII historian who also works with Roma Experience. Our first stop was the Fosse Ardeatine, the site of a massacre ordered by S.S. Lieutenant Herbert Kappler as retribution for the attack in Via Rasella. For every Nazi soldier killed, they murdered ten Italians, most of whom had nothing to do with the attack, and left them in a mass grave.

When the corpses were discovered a few days later, they were identified and laid to rest side by side there, their graves marked with their names and occupations. As we walked solemnly through the rows of graves, we saw brothers or even whole families buried next to each other.

If that wasn’t harrowing enough, we then went to the Museo Storico della Liberazione inside the jail on Via Tasso where the S.S. tortured prisoners to try to get them to speak. Valerio, whose grandfather fought with the partisans, told us about the heinous methods the Germans used to break people. Inside the cells where dozens of prisoners were kept together, there are posters that the Nazis hung around town, letters the prisoners wrote to their families, photographs, and even blood stained clothes.

That evening, we had dinner at Pommidoro dal 1890, a family-run restaurant in San Lorenzo that was bombed during the war and later reopened in its current location. Though Rome was declared an Open City to spare its historic monuments, the neighborhood of San Lorenzo was bombed because it’s so close to Termini Station and the railway. We skipped dessert at Pommidoro and instead went to SAID dal 1923, a chocolate factory that was also bombed during the war but is now a must-visit stop in the neighborhood.

Further Reading

The full August issue of Hemispheres is available to read here. Flip to page 96 to read my feature.

This was my third visit to the Reggia di Caserta and my second time dining at I Masanielli. I wrote about both in issue #46: Is Caserta—Home to Italy’s Best Pizzeria and a Royal Palace—Worth a Detour?

In case you missed it, I wrote about commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Rome in issue #88.

Looking for a great guide in Rome? Read my interview with Elisa Valeria Bove, who organizes bespoke tours of the city, including WWII-focused tours.

Believe it or not, I learned about Pommidoro through Stanley Tucci. The restaurant is featured in the Rome episode of his CNN show, “Searching for Italy.” You can see a list of all the locations featured in the first season here.

Ready for a deep dive into the Italian campaign during WWII? You might want to read Crossing the Rapido: A Tragedy of World War II by Duane Schultz, which is available on Amazon.

What an amazing trip! My grandfather was stationed in Italy from December 1946 to November 1947 when he was 18. He recently passed away and in going through his things we found all of the letter he wrote to my grandma during his year there (he left three weeks after they had met!). I knew he was at first based in caserta at the palace but discovered he then moved on to leghorn which research shows me was Livorno. The letters and photos document his travels and experiences as well as the country in the immediate postwar period. Would love to do a similar trip with my whole family!

So many incredible stories and emotional moments here, but that attic in Caserta looks particularly unforgettable. Wonderful post!