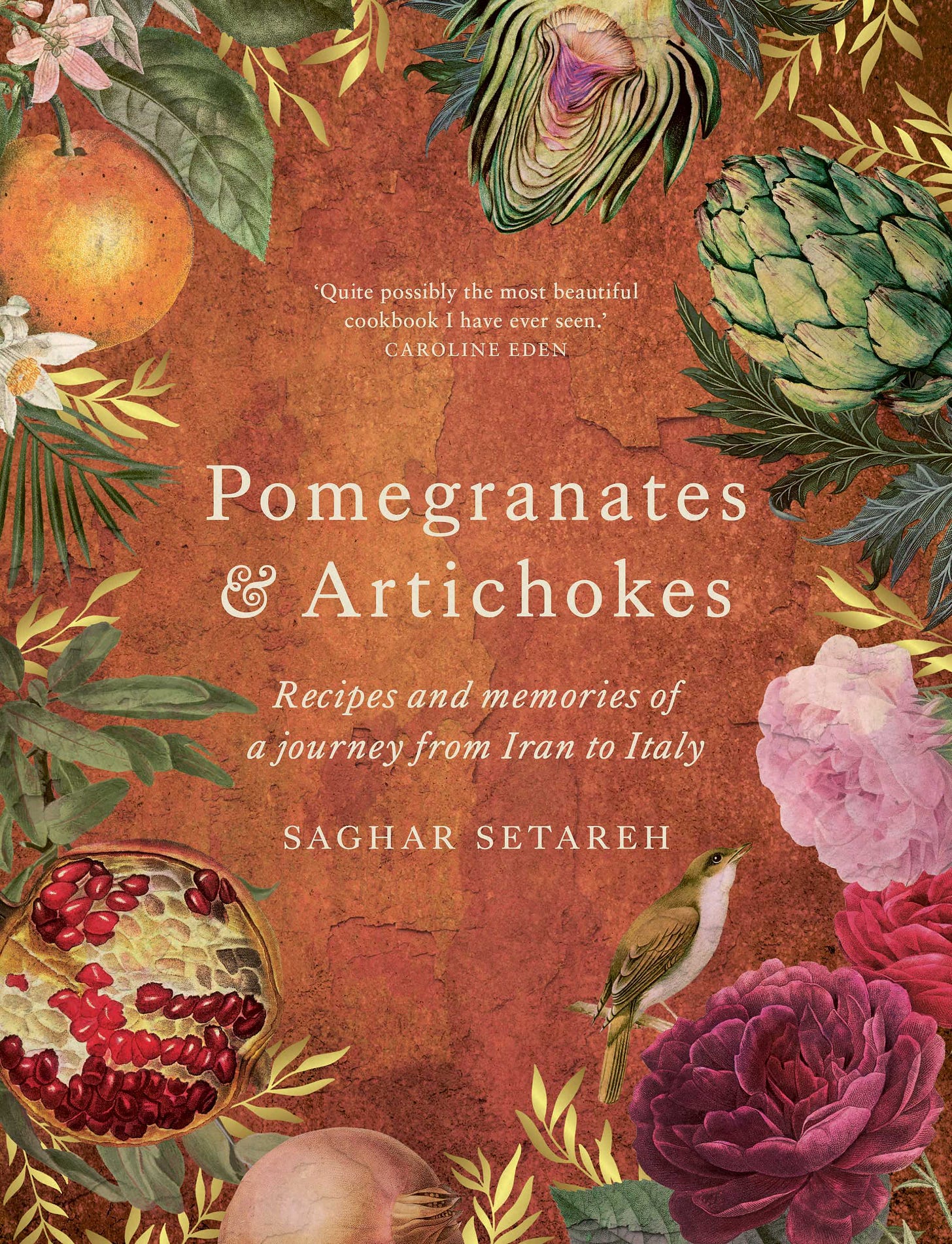

An incredibly talented photographer, graphic designer, and writer, Saghar Setareh moved from Tehran to Rome at the age of 22 and has been living here for 16 years. Her debut cookbook, Pomegranates & Artichokes: Recipes and Memories of a Journey from Iran to Italy, was released in the U.K. earlier this month and will come out in the U.S. next month. Divided into three sections focused on Iran, In Between, and Italy, it tells the story of her own culinary journey, starting in Iran and traveling west through the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean, ending up in Italy. As she describes it, "It's a quest for things that link the people of these lands, rather than separate them."

I first met Saghar through a press event in Rome and have gotten to know her and her incredible work over the last few years. Luckily for me, though she doesn’t typically do wedding photography, she agreed to photograph my wedding. I have attended one of her Iranian cooking classes, an Iranian dinner she helped organize to raise funds for protesters injured during the Woman, Life, Freedom revolution in Iran, and her book launch event in Rome, and always look forward to reading her Substack,

, which is the evolution of her popular blog Lab Noon. I’m thrilled to share her story as part of my series of interviews with creatives and entrepreneurs in Italy.Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview and congratulations on your book. I want to talk all about the book, but before we get into that, I thought it might be nice for my readers who don't know you to get into your story about coming here. One of the things you write in the book is that you came to Italy for university, and you weren’t fleeing persecution or violence, you came like young people from all over the world move to other places, but I’m curious to know a little bit more. How did you end up here in Rome and not in, say, Paris or London?

Thank you so much for this interview. I’m so happy to be talking to you about all of these things. I came to Rome at the age of 22. It was 2007. I came on the 23rd of August and on the 21st of August, I had graduated from university in graphic design. So it was that age that you can do these sorts of crazy things. From the time I can remember, possibly since I was a teenager, I always had this fantasy of going abroad and living on my own—a fantasy based on movies and sitcoms or things like that.

Another part of it was, like a lot of Iranians, we all have family members abroad. Because of the things that have happened, there have always been these huge waves of migrations outside of Iran, especially with the Revolution of 1979. So for example, I have four uncles in Sweden who have been living there since the mid ‘70s and then sometime in the very early 2000s, one of my aunts moved to Germany. So this is a very common idea, especially for young people to go abroad for study or for other things.

The more time has passed, this has become more of an emergency. So of course, with the Revolution of ‘79 and the war with Iraq in the ‘80s, this was really a matter of emergency. People moved in all possible ways. There was also a huge wave of refugees. I would say perhaps in the ‘90s and early 2000s, it had calmed down, but in the late 2000s it picked up again. And as the situation in Iran has been getting worse and worse and worse, more people have been trying to get out, naturally.

Personally speaking, I had this desire and I should say that as unhappy as I was with a lot of things happening on a social and political level in Iran, this was a personal matter. I wanted to change my life settings.

Like so many people do...

Exactly. It’s a very tricky point because I don't want to say that everything else was fine in Iran and I just wanted to leave because of my family or the way I wanted to live. They were interlinked, but at that moment I wasn’t facing particular hardship in Iran. I wasn't escaping war. But especially with the revolution of Woman, Life, Freedom happening since last September... When this happened, I had already finished the book, but it kind of made me wonder, when I say I wasn't escaping anything, was I really not escaping anything? Because in a way I was.

You had the compulsory hijab, right?

Of course, we had the compulsory hijab and the whole lifestyle that had been influenced by the existence of the Islamic Republic.

So when you came here, did you find it difficult to make that transition or did you kind of just tear the hijab off?

It’s never difficult because the majority of Iranians have all suffered from the compulsory hijab and we have always lived a double life. That’s why people now are so fed up. They don’t want to live the double life anymore. It’s so exhausting.

So when you say double life you mean public versus private?

Exactly, because we never wore a hijab in private occasions. We would dance and have a drink, which is illegal. We would do all of those things which outside we’d be punished for. So it was very easy to go out and just not do it anymore. Perhaps like 15, 20 years ago, for a moment you would think, what should I wear when I go out? Because we were forced to cover ourselves up. So we would have our clothes under that manteau, but now for many years they don’t dress like that in Iran. The manteaus are open. So you would have a nice shirt underneath.

So if you were going to a party or to a friend’s house, you would have your nice outfit underneath and when you arrived, you would just take the manteau off?

Exactly, so when I say now that I wasn’t escaping anything because I wasn't personally under persecution, it means that I didn't have a literal case in the tribunal or something. But this is something I remember with this revolution and I took a mental note that I need to explain this because it might come off the wrong way in the book. And the other part of it is that despite all of these things, which were undoubtedly very hard, the same way that people go on Erasmus, it was somehow the same thing.

So when you came here, you already had a degree in graphic design from...

It’s called Azod. It’s the art and architecture faculty.

In Tehran?

Yes.

And so when you came here, what was the degree you were working toward at that point?

This was very funny because I graduated literally two days before flying out. This was in August. I had sent my documents to the Italian universities in May, so back in May I hadn’t had any university degree, I just had my high school diploma. And I said, “You know what, who cares? I can start over again.” So I did that and that’s a very long story actually. Initially I wanted to get into a faculty of architecture, which back then had a multimedia and design course, but when I arrived in Italy, they told us, “Oh that course doesn’t exist anymore” in a very Italian way.

So what did you end up doing your degree in?

I went to the Fine Art Academy, Accademia di Belle Arti after a lot of troubles, but I’m very glad that I did.

Was that still in graphic design?

It was first in editorial design, which is a kind of graphic design but more towards editorial. And then I did a masters course in graphic design and photography.

You have such a good eye—both as a photographer and a designer—and I can speak to both having seen your work in the book but also photographing my wedding, which was amazing.

Thank you! That was a real honor.

But to get back to that period, you came here and got a student visa. How did you decide to stay? What was your plan at that point?

Once I got my student visa and I came, I knew I was not going back. But before this thing happened to me, I had never considered Italy in my life.

Were you thinking of other places, like Paris? London?

To be honest, I can’t remember what I was thinking, but I remember it was Europe. I didn’t have this fantasy of the United States or Canada that a lot of people did, or Dubai for example. It was never Italy. It might have been Germany because I was very much obsessed with everything about Germany in those years. I ended up in Italy as the indirect result of a bet that I made on the Italy Germany World Cup match in 2006, which Germany lost and Italy won and this was the semi-finals and then in the finals, Italy won the actual World Cup.

So you bet on Germany?

Yes.

And Germany lost, so you went to Italy?

I was going to this class in aesthetics and art philosophy with one of my university professors who was very popular. I could never get into his drawing and illustration classes, but I went to his aesthetics and art philosophy class and I loved it a lot. He had this private atelier, so I went there and I didn't know anybody, maybe two or three people from university. I would go there, not speak to anyone and just get out of there. It was like this until the World Cup started.

When the World Cup started, all these walls came crumbling down because each of us was rooting for some country because in Iran we all root very hardcore for Italy or Brazil or Argentina or something. And I had been a Germany fan for a very long time and this one was in Germany and I was very sure that this was finally Germany’s year. And I remember I got into talking about it and there was this guy who said, “You know what, let’s make a bet. Whoever loses takes the other one to lunch.”

And I will never forget this, the match was on a Tuesday night and I had the class on Wednesday morning, so I kind of didn't want to go there. And this guy who back at the time was about my age, maybe a year older, wasn’t in university and we’re a very educationalist society in Iran and in my view, he wasn't really doing anything. So we get a sandwich or something and for the first time we started talking and I asked him, “What do you do?” And he said, “In a couple of months, I’m going to italy.” Now, this is very important because getting outside of Iran is very difficult for us, not because somebody is taking you inside Iran and saying you shouldn't leave, but because no one lets us in.

You need to apply for a visa...

You need to apply for a visa, you need a lot of money, you need a lot of time. And in order to get a visa, you need to prove a billion things. Like see me, after 16 years, I need to go to the U.K. to promote my own book. My editor and my agent have to send me the invitation, they are guaranteeing that I’m not staying there and I will come back and all of these things. So for someone who in my opinion wasn’t doing anything, not even studying, this sounded too good to be true.

So I asked him, “How did you do that?” And he said, “Oh you know, there’s an Italian school that’s part of the Italian Embassy. You go there, you study some Italian and then you can apply for university." And he was like, “I think maybe Institut Goethe is doing the same thing for Germany, so perhaps you can try to go to Germany.”

And that day—I will never forget this—I went home, I didn't know if Institut Goethe was doing something similar, but I said to my father, “Papa, can I study German and go to Germany?” And he said, “Sure, go ahead.” It was such a far fetched idea that my father was like, go ahead. And a few weeks later, I heard the same thing from one of my colleagues. I used to teach English back then at a language school and one of my colleagues who was my age was saying the exact same thing. And I thought, “Oh my god, maybe this thing is really happening.”

And in about a month or two, the original guy was leaving and he invited me to his goodbye party and he gave me the number of his private tutor. And once I figured out that this can happen, I decided I am doing this and I am going away. And I don't think I have ever studied for anything as hard in my life as I did for that exam because I really wanted to get out.

So at what point did you realize that it was Italy, not Germany?

This point. Exactly this point.

Because these other people were getting visas to go to Italy?

I never figured out if Germany was doing something similar or not. Probably not because it would have been a lot easier. So at that moment, Italy was incredibly easy and relatively cheap, so I didn't care anymore that it was Italy, Germany or somewhere else. It was within my reach. And I did everything I could to make it happen. And the reason I chose Rome was very simply that it was the capital city. And in my head, living in Tehran, I thought Tehran is the best city in Iran, so Rome should be the best city in italy.

Do you still feel that way?

I like Rome and I’ve never lived anywhere else in Italy and I wouldn’t move at this moment, but perhaps back then if I had known, I would have chosen to go to Milan.

But that was more than 10 years ago, no?

That was 16 years ago.

So I think Milan was quite different then. Milan has changed a lot.

Exactly. But the moment I came to Rome, I madly fell in love with it. It wasn't anything that I had expected because at that moment, I was so consumed with the idea of getting outside Iran that I hadn’t thought about where I’m going, what I'm doing. All of these fantasies that people have about going to Italy, I didn't have them and I didnt even know about them. The only thing I knew about Italy was some of the football players.

So you were saying that once you arrived and you were working on the degree, you knew you weren’t going back, right?

Even before I arrived. Once I had the visa, I knew I had my ticket out so I wasn't going back.

So once you finished the degree, how did you make that work? Because going from a student life to a professional life is a whole other transition, right? Aside from moving to a completely different country, just the fact that you’re no longer a student and you need to figure out how to support yourself, what was that transition like?

That’s actually a very good question, nobody asks that. So I arrived with a tiny bit of money and I knew that I had to work also as a student, like all of the other Iranian students I know. So I did a few things that students do. I also had a scholarship, so that helped a little bit undoubtedly, but I did work. I taught a lot of English.

When did you start your blog? When did you make the transition to blogging and photography?

That was quite a bit later. I always knew that I had to convert my student visa to a work visa, so that was a thing of its own. There was a practical side of it. And at a certain point, around 2011, 2012, I went on a very strict diet. I had the gastric balloon put inside my stomach and I went on this really crazy insane diet. And I was obsessed with cooking. And this is how I discovered food blogs and these were the earliest days of Instagram.

So I had started—nobody knows this about me—but the first ever recipes that I shared were all of these crazy light diet recipes with calories. It was a crazy period because no one who knows me from recent years can ever associate me with that, with someone who weighs 40 kilos less than this and was on a crazy 1,000 calorie diet a day. But this is how I came upon food. And I discovered some very interesting food blogs.

And small parenthesis, I had photography classes at my university in Iran and then a little bit later when I came to university here. Anyway, I hated photography, I couldn’t understand photography. I couldn’t understand the point because my high school diploma is in mathematics and physics so when I went to university in Iran, I was still in that space. I had learned how to use a camera, but I was terrible at it.

So flash forward to 2012, 2013, the balloon had come out and I was determined to keep the weight down, I came upon some very good food blogs. Some of them now are the best culinary authors we know. So we’re talking about early Instagram and I remember this thing that I thought, I can do this because I knew how to make a composition. So there’s a little back story to this, that in all of these years although I really wanted to do something creative and I came from this atmosphere where I had a lot of artist friends, I can’t say I had strived to become an artist, but I tried to be good at illustration and I kind of felt like it doesn’t come to me. But I remember that I had this thing that I can do this because this is about food and I like food.

And while I was doing these crazy diet things, I understood that I really liked food, and not just food as in the recipe but food as something you do. You do something around food. I really liked that. I was very inspired by some of the things I saw, and not just because they were beautiful but because I loved working with this. And then I decided to do the blog.

One of the things I thought was interesting in your book is how you say that coming to Italy, even if everything else around you is foreign, dinner has to feel familiar, right? So there was something about cooking, but not just cooking in general, it was what you were cooking. You were cooking Iranian recipes. So do you still cook mostly Iranian recipes? Do you cook a lot of Italian recipes?

That part of the book is also about duality. There are those moments that you realize that everything is different but dinner has to be the same. But there are also those moments when you think, “You know what, I’m a part of this so I’m going to cook this.”

I feel the same. I’m also an immigrant like you and it’s obviously a different situation, but I cook a lot at home and mostly I cook Italian food, but for some reason, I can't let go of this idea of an American brunch and I need to have eggs on the weekends.

Why should you? I understand. Well, now is a very particular moment in my life because I’m not cooking at all, but something I’ve noticed is that Iranian food for me has always belonged to a big group of people, whether it was a cooking class or my Italian friends for whom I wanted to cook Iranian, or with a big group of Iranian friends gathering around. It’s very difficult for me to cook Iranian food for myself alone. In general, I don’t cook Iranian food for just me because it’s too difficult. I don’t have an attachment to Iranian food, but I do enjoy it when people say, “Let’s gather and make such and such.”

So are there any recipes in the book that you cook on a regular basis?

Funny enough, it’s mostly the recipes from the In Between chapter because I feel very at home in that place.

For example?

The dips. The baba ganoush or moutabal, which is with eggplants. The muhammara, which is with bell peppers. And then I also love this thing which might look underrated because it doesn’t have a photo of the recipe, the Circassian chicken. And then from the Italy chapter, there is this bucatini marinated with tomatoes which I go back to that’s very good. In the Iran chapter, all the yogurts of course. And then there’s this pilaf with green beans, which it’s actually the season.

So I remember meeting you a couple of years ago, we were sort of coming out of the pandemic, starting to go to some events again, and I remember that one of the first things you told me was that you were trying to sell this book. So where did the idea actually come from?

I would say people who blog about food, especially in those years, a lot of them secretly or perhaps not so secretly have the idea of writing a cookbook. Professionally, I really wanted to do this since the first years that I started blogging. And I was under this impression, like so many other people around me, that if I simply kept doing what I was doing, an agent or a publisher would come to me with a book.

It doesn't really work that way does it?

No, it doesn’t. If you're a star, or you were in those years because the definition of a star changes, it may happen. I did have a couple of publishers coming to me. What they offered wasn't something I wanted to do. And then there was a moment when I realized I needed study how to write a cookbook. And the first thing that they said was you need to have a good niche idea and there was a moment when I was like, “So what is a niche idea?” I have actually written an article about this. It will come out sometime in July perhaps.

I know you’ve written a bit about the process also on your substack.

The process is very practical and pragmatic, whereas the idea was a very mystical experience because what I did was I prayed on it. And to this day it has been one of the most amazing experiences of my life because it came to me like this, “You already know it because you have already done it.”

And I had already done it because in that graphic editorial course at the Belle Arti, I did the thesis well and it was called the “Tale of Two Cities,” about Tehran and Rome. And aesthetically speaking it wasn’t amazing, it was good, but there were a lot of narrative pieces in that booklet, which is very similar to this book.

And actually this book, Pomegranates & Artichokes, opens with a quote which is a poem by Mahmud Darwish. A larger part of that poem is present in that thesis. And by the time I did the thesis for the masters, I had already been blogging and that was a cookbook prototype, but it didn't have anything to do with Pomegranates & Artichokes conceptually speaking. From an aesthetic point of view, it was beautiful, but it didn’t have the content. The other one had the content.

I think the idea is so compelling because it works on two levels: this is your personal journey, you’re telling your narrative, but it also works historically in a lot of ways, right? If you think about the way food travels.

Food has always traveled. Nowadays we have this idea of super regionalism, which is true, nobody is saying that it’s not true, but it doesn't mean that it’s been isolated.

It’s not the whole story.

There are other similar things around it...

Like there was that whole controversy recently...

The article in the Financial Times?

The thing about the carbonara.

Yeah, and if anybody reads about the carbonara a little bit, they wouldn’t be surprised that it’s a very new mix. The same thing with tiramisù. There is no written record of tiramisù before the 1960s. So nobody can say, “This is the original, you can’t mix it.” Because you mix foods and you mix people too. If you say that they shouldn’t be mixed, it doesn't mean they won’t be mixed. They have always been mixed and they will be. So I thought it was very interesting.

When I had this idea, I have to be honest, I didn't think there would be so many historical connections. I thought, “Okay, same climate, same ingredients, same problem, same solution?” Possibly something like this. And I didn't dig into all of the dishes historically speaking because I didn't want to do an academic research. I’m sure if I had time, I would have found even more things. But I really wanted to put some personal stories in, my own stories and the stories of other people.

But I think you make the connections and part of that is to show the commonalities. Part of that is to show that yes, Iran and Italy are different countries and different cultures, but they have more in common than people think.

Exactly, and I say this about Iran and Italy because I’m from Iran and I live in Italy, but also because I believe there’s a bureaucratic fence that is not limited to Iran. It’s my side of the world and this side of the world. You can move to a certain degree, but don’t you dare put your foot above that other part because if you do you need to pay a very huge price. You either need to spend a lot of money, a lot of time, humiliation, effort, to be able to get on the other side. Especially people fleeing war.

I remember when Russia first invaded Ukraine last year, a lot of Iranians, or not just Iranians—Palestinians, Afghans, a lot of people from outside—we went through hell because everything was triggering. I remember I saw these windows with tape in an X form on them and I collapsed because I remember them from my childhood because when Tehran was being bombarded, we would have these tapes on the windows because even if it’s bombarded from a kilometer away, windows still break. So we had these things so the windows wouldn’t break inside the house.

And I remember my house, there was a moment when all of the windows were broken. The curtain of my bedroom, which had little dolls on it, had been completely ripped apart by one of these shards of glass and the air conditioner had been thrown in and my mother for years used pieces of this curtain as kitchen cloth and for years we had memories of this horrible trauma in our kitchen. So anyway, these were the things that we had experienced and the first reaction of the global media was, “Oh but these are real refugees and it’s unimaginable. It’s not like the other places.”

Because it’s Europe?

Because they’re white and they’re Christian. And I remember the bombs that were set on us were funded by this part of the world. And second, you do all of these things to us and then we are the ones who relive the trauma and you dare tell us that these are real refugees as if our pain didn’t matter?

I wrote the last pieces of the book exactly at this time. It was the end of February, beginning of March 2022. And I tried to fit it in, I don't know if anyone can read it. But it was a lot about this. Like my friend from Syria. She can’t go back to Syria. She has a PhD in archeology from La Sapienza, but she couldn’t find one single job in Europe because she’s a Syrian passport holder. And this was something I really wanted to bring out. That we have so much in common and the only thing separating us is these bureaucratic laws.

I remember you saying during the presentation that it’s a cookbook, which in theory isn’t political, but it is political.

It is political. I hope it reads as a political book because honestly if that part of the book doesn't come through, I have failed in what I wanted to do. So I hope that comes through.

I think you do a really lovely job of writing about the immigrant experience, about the Iranian experience, and this duality of inhabiting these two cultures and constantly having to explain yourself.

Exactly, because that’s another thing. I really want to feel that I belong here and on my own I do feel like I belong here. Whenever I go outside Italy to anywhere else... You know, Rome is such an amazing place that you can’t ever be really surprised, like, “Oh yes, this is nice, but we have this.” So I count myself into that.

So whenever I’m reminded that I’m not a part of that, it’s heartbreaking to me. And you know, especially with Italians—I’ve never lived anywhere else, so I don't know how it’s done elsewhere—but here in Italy it’s like “Ciao, come stai?” And the second question is always “Di dove sei? Where are you from?” So it’s kind of a reminder that you don't belong here.

And then they ask, “Are you going to stay?”

No, they don't ask me this.

They ask me.

Yes, because you're an American. They ask me, “Why did you come here?” So you need to justify yourself. But I don’t know how it’s done in other places. Actually it was in my last therapy session, my therapist was insisting “Why do you confuse this interest as an accusation that you don't belong here?” And we had a huge disagreement about this. So perhaps it is an interest, but I always feel like the place you come from comes before the person that you are.

I don’t know if it’s despite or because of your status as an immigrant, but it seems like the reception of the book here has been quite good, right? You’ve been featured in Il Corriere, in Italy Magazine, in some other articles. How are you feeling about the reception of the book?

I am feeling delighted and very grateful because a lot of effort and energy has been put into this book, not just by me but by the whole team that has been working on the book. And to be honest, I don't even have a measure of comparison. I don’t understand whether it’s something very good about the book or is it something that happens to all books? I don't know, but I am very happy so far because a lot of people like yourself say, “Let’s do something about the book.” This is very nice.

It’s been in Corriere della Sera, who are always very generous to me and they have also invited me to be part of their event called Women in Food in September. And we have the Italian edition of the book coming out in late September or early October. This is another thing I’m incredibly grateful for because these sorts of cookbooks—cookbooks written in Italy perhaps completely or partly about Italy—almost never are translated into Italian, which I understand is a matter of the market and the audience and all that and I’m just over the moon that Slow Food Editore has picked up the book. Slow Food is the dream.

Has your family seen the book?

No, they have not seen the book. To be perfectly honest, I don’t really think they understand the magnitude of the thing, which is fine, it’s okay.

I think you told me they don't speak English, right?

They don’t.

But I would imagine they would at least be curious to see the book.

I think they would perhaps like to see a book with my name on it. I know they’re happy and they’re proud, but I don't think they completely grasp the situation. I have friends here in Italy that don’t completely understand, but it’s fine because they’re not in this world. But it was featured in the Guardian, which caught me completely off guard because I didn't know about that. It’s featured on Nigella Lawson’s cookbook corner.

So what are the events you’re planning to promote the book?

I’ve started this series, Pomegranates & Artichokes supper clubs. The first one is happening in Milan in collaboration with a dear friend of mine called Mona Bavar, who has this amazing gifting company. She creates gifts with artisan handmade Italian products.

We’re doing this dinner on the 14th of June and then I have a cooking class with

in San Miniato at her new Enoteca Marilu and we’re gonna have a book signing in Rome I believe on June 11th at Otherwise Bookshop. We’re gonna have a book signing in Florence hopefully the day before the cooking class in San Miniato, so the 26th of May. The cooking class is on the 27th.And then on June 21st, I’m going to London. We have a couple of events at festivals on the 22nd, 23rd, and 25th, and on the 28th we are having a presentation at Books for Cooks in Notting Hill. We will probably have some more events, but I need to get my head around the situation.

And remind me when will it come out in the United States?

The American edition comes out on June 20th for Interlinks Publishing, which has a slightly different cover. Everything else is the same.

Is it available for pre-order?

It is.

So wrapping up, can you share a few of your favorite places to eat in Rome?

Yes, so they change, but at the moment I am very much obsessed with Piatto Romano in Testaccio. They have the most amazing vegetables. They have the classics, but what is amazing about Piatto Romano is they actually go to the field or they buy their vegetables from people who harvest them from the field and they have vegetables with names that you haven’t even heard of.

Then I really love eating more at wine shops and enoteche than restaurants. This place we’re at now. It’s called Machiavelli 64, it’s on Via Machiavelli, which is a very nice street at the moment. I love Forno Conti, which is a breakfast place and we also have some collaborations. I love Da Tonino, which is a trattoria in Via del Governo Vecchio. And I love Marigold. Marigold is always Marigold.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Further Reading

To get to know Saghar better, you should subscribe to her Substack newsletter

and follow her on Instagram @labnoon.You can find all the links to pre-order the U.S. edition of the Pomegranates & Artichokes here. If you live in the U.K., Europe, or Australia, you can order the U.K. version here.

Saghar was recently featured in this wonderful interview with Italy Magazine.

Saghar’s recipe for saffron and lemon toasted pistachios was featured on Epicurious.

A few of the recipes from the book were featured in The Guardian.

She was featured as one of 50 Women in Food by Il Correire della Sera (in Italian).